Dr David Comerford, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Stirling Management School

On the evening of Monday, March 15th the lead story on the UK nightly news was that various European countries, including France, Germany and Italy, had suspended use of the AstraZeneca vaccine because of links to blood clots and deaths. The following day, the story was front page news across the board, from the left-leaning Guardian to the right-leaning Telegraph, from the Daily Mail to the Financial Times. How did the public respond to this news?

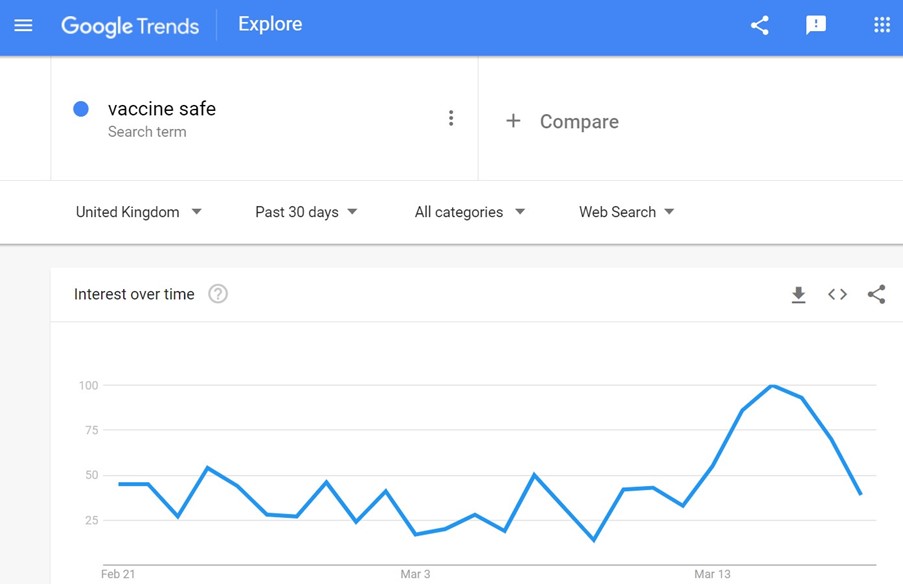

Initially, with concern. Google Trends data shows increasing search activity for the items ‘vaccine’ and ‘safe’ as the AstraZeneca suspension story was unfolding.

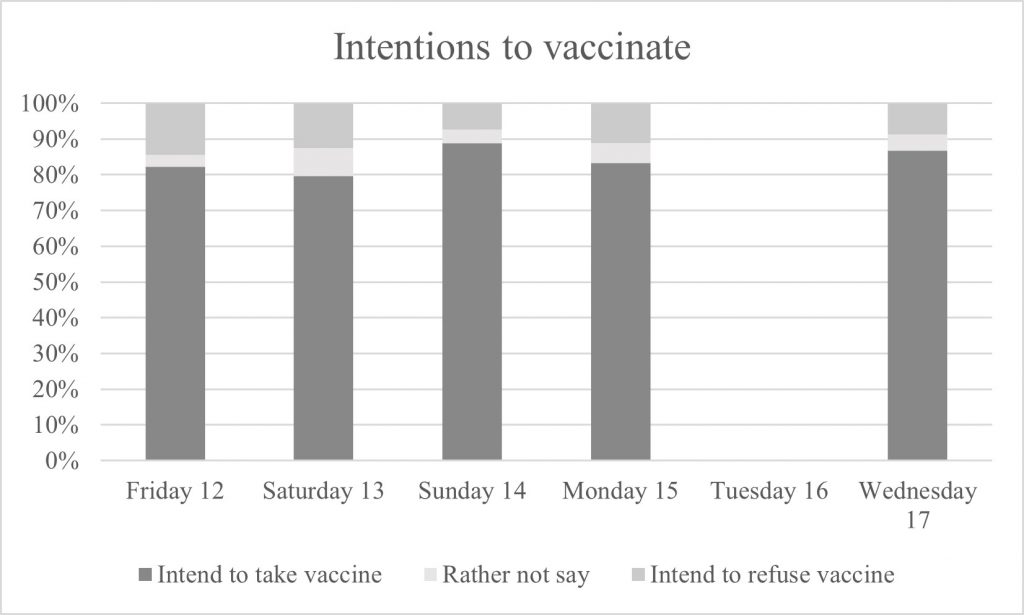

What were the consequences for the program to vaccinate the UK public against Covid? We happened to be in a unique position to observe. In the period immediately surrounding these events, we were collecting survey data for a project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), as part of UK Research and Innovation’s rapid response to Covid-19. We did not realise when we started data collection that effectively we were capturing time-lapse footage of the public’s response to the story.

The data show no effect of the news story on intentions to take the vaccine or on intentions to refuse it. Furthermore, there was no change to the perceived costs and benefits of the being vaccinated, as measured by three attitude items. (The full paper is available as a preprint here).

These results are reassuring – they suggest that public confidence in the vaccination program remains strong within the UK. We note, however, emerging evidence that confidence in the vaccination program among European residents was damaged by these events. An important question for future research is why the UK and European public responded differently and whether there are any lessons that can be learnt to manage future scare stories.

Possible Lessons

We can only speculate but one factor that might have buffered the British public against a scare story of this type is some excellent communication by health authorities.

Good communication is especially important in the domain of vaccination because vaccination is emotive, politically charged, psychologically complex and has been beset by an infamous case of scientific fraud. At a time when people are afraid and fake news abounds, it was vital that the authorities got their communication just right. At a bare minimum, this means avoiding reckless language. France’s President Macron did damage when he declared last month that the AstraZeneca vaccine was “almost ineffective” in the over-65s.

But good communication is about more than merely avoiding untruths. It is about making one’s message intuitive. A telling insight comes from alcohol education research, where it was found that statistics are more persuasive than anecdotes when preaching to the converted, but the reverse is the case when speaking to sceptics. A neat example of how the UK has been strong on health communication is that this time last year we were taught to wash our hands for 20 seconds by singing “Happy Birthday” twice.

Right from the outset, the UK has been a world leader in all aspects of vaccination; not merely in developing the vaccines but also in administering them. Perhaps relatedly, the UK was also an early leader on reassuring the public that vaccine safety was paramount. Back in November, Deputy Chief Medical Office Jonathan Van Tam invoked the “Mum Test” to make this point. Instead of drawing on statistics or his authority as an expert, Van Tam made it personal. He said “I’ve already said to her, ‘Mum, make sure when you’re called you’re ready, be ready to take this up, this is really important for you because of your age.’” Not only will the mention of the word “mum” have evoked positive neurological responses in listeners. His story also gave his audience a sticky and meaningful representation of just how safe this vaccine must be before being scaled up for release.

Perhaps communication like this, with its implicit message that our medical authorities are staffed by competent and humane individuals, might have played a role in causing the UK public to respond so assuredly when other populations did not. After all, just a few days after the blood clot story hit the headlines, the UK set a new record for number of people vaccinated in a single day.