Dr Steve Rolfe – Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Stirling

Today saw the launch of a new housing policy group within the Social Policy Association, the professional association for lecturers, researchers, and students of social policy in the UK and internationally. This new group, co-chaired by myself and colleagues Dr Vikki McCall and Dr Peter Matthews, from Stirling’s Faculty of Social Sciences, will explore issues around diversity in housing, inequalities and social policy integration.

The challenges and opportunities represented by these themes were set out in a blog first published on the Social Policy Association blog, (16th April 2021) and reposted below.

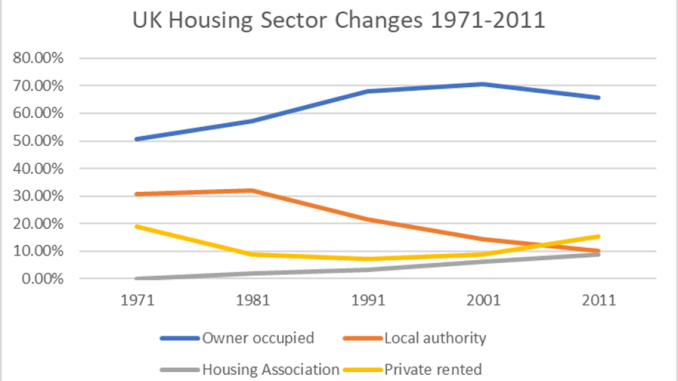

Narratives of housing and social policy, particularly in the UK, tend to focus on the growth of state activity in the delivery of housing from 1945 to 1980. However, the last 40 years have seen a marked change in the role of housing in policy, the economy and society. The financialisation of housing has normalised owner-occupation as the tenure of choice in much of the Global North. Within the UK, policy has directly and indirectly supported the growth of private-renting as a tenure, even though this is extremely poorly regulated. The growth in housing wealth, and the high levels of housing supply in the late twentieth century, have also led to those owning their home outright, unencumbered by mortgage debt, are now the largest tenure.

The housing sector is persistently perceived as being in some sort of ‘crisis’. For Social Policy academics interested in housing, it is also viewed as the ‘wobbly pillar’ of the welfare state. This makes it a challenging area for social policy. However, these recent trends in housing in the UK mean it must be a key focus of Social Policy. We have a bifurcation between people on low-incomes struggling to pay rent in poor quality, privately-rented accommodation (“generation rent” is now increasingly a phenomenon of all age groups) and a group of older owner occupiers with large housing wealth who are increasingly expected to use this asset to pay for their welfare and care in older-age. For those lucky enough to be able to live in the remnants of social housing, as with the rest of the welfare state, this support is increasingly conditional and policed.

Housing and welfare reform

Within the broader debate on the UK housing sector as a whole, the experience of low-income households is one of perpetual crisis – a perfect storm of under-supply, unaffordability, and welfare reform. Over the past decade the welfare reform agenda has multiplied the challenges for low-income tenants in both social housing and the private rented sector (PRS), including:

The ‘bedroom tax’ – cutting Housing Benefit for ‘under-occupancy’ in social housing

Benefit and rent caps – restricting total benefits or the amount of rent eligible

Sanctions and suspension of benefits – imposing strict conditionality on job seekers

These changes, combined with the shift away from direct payment of rent, also create difficulties for social and private landlords struggling to collect rent. And the impacts of the pandemic have only exacerbated the problems – whilst evictions have been paused during lockdown, there are growing fears of an arrears crisis impacting on rental incomes and potentially leading to large numbers of evictions. All of these issues undermine the already weak foundations for the wobbly pillar, reinforcing inequality.

The picture is not, however, uniform across the UK. Aside from substantial geographic differences in housing costs, particularly between London/South East England and everywhere else, there is significant policy divergence between the devolved administrations. The Scottish Government in particular has attempted to rebuild the basis of social housing through ending the right to buy, mitigating the bedroom tax through Discretionary Housing Payments, investing heavily in affordable and social housing supply and setting out a 20-year route map based on principles of ‘social justice, equality and human rights’.

Housing, health and care

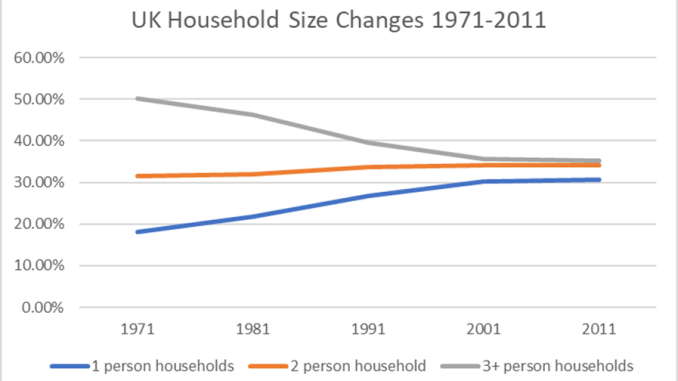

The housing pillar is crucial in buttressing the health and social care elements of the welfare state. As the population ages and the proportion of people living alone increases, there is an increasing need to consider the adequacy of current housing stock in terms of accessibility and adaptability and the extent to which the current housing delivery pipeline, dominated by a sclerotic construction industry, is capable of delivering appropriate, good quality, well located homes.

At a more fundamental level, there is now a robust evidence base that demonstrates the role of housing as a social determinant of health, not only through the obvious physical health effects of housing defects such as damp or mould, but also through more complex processes related to different aspects of housing provision and services. Crucially in the current context, there is emerging evidence that the pandemic is reinforcing inequalities in housing and poor-quality homes have contributed to the pandemic. For social policy, therefore, housing has now been cast as an explicit tool to tackle COVID-19.

Looking beyond Beveridge

Our argument is that housing should be at the core of the welfare state, not merely in its own right as a basic human need, but also because of the interactions between housing and other crucial issues, including poverty, inequality, health and wellbeing. The failings of current housing policy across the UK are brought into stark relief if we consider Gandhi’s suggestion that ‘the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members’. At the extremities of social exclusion, people seeking asylum in the UK from oppression elsewhere in the world find themselves forced into squalid housing, or held in former army barracks which are almost designed for viral transmission.

Moreover, housing plays a central role in processes which extend beyond individual households. At a neighbourhood level, local and national housing policy shapes the nature and experience of community, influencing social support and ultimately wellbeing. And at a national and global level, the very fabric of our housing stock is a key factor in driving climate change. To ensure that we have a liveable planet and homes that can cope with the climate change we are already experiencing, radical policy change is essential. As with other social policy sectors, this means confronting head-on, the complex (and classic) ‘housing question’ of who should deliver the homes of the future and on what ‘value’ basis, as the pressing questions of scale, affordability and quality interlock.

As colleagues have argued on this blog, the current crisis caused by the pandemic highlights the need for a new Beveridge report, future proofing the welfare state to ‘build back better’. Whoever might be the architect for such a project, they will need to start by rebuilding the foundations of the wobbly pillar and placing housing at the heart of the welfare state.

To keep up to speed with the work of the group, follow @HousingSPA on twitter.