Professor Andrew Watterson, Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences and Sport

Andrew Watterson argues that failures in worker health and public health planning have collided with devastating effect. This blog draws upon a research report, available here.

Occupational health and safety, a reserved matter, has been a Cinderella in the funding and staffing policies and practices of successive UK governments. Worse than that it has been a specific target in the last decade or more for those wishing to cut red tape. In the argot of the time this meant to deregulate or, in the softer versions, to ‘better regulate’ or ‘smarter regulate’. These policies have damaged inspections, monitoring, information and advice and enforcement on workplace risks arising from established hazards at a time when thousands of workers each year were already dying from occupational diseases and millions had their health damaged by work-caused or work-related factors.

Running parallel with these cuts and ideological attacks have come significant cuts in the National Health Service, most pronounced in England but biting across the whole of the UK in terms of staffing and resources. Juxtaposition these two elements with the possibility of a pandemic which could take out key workers in acute, primary and social care, and also from key parts of our economy, and a perfect storm looms.

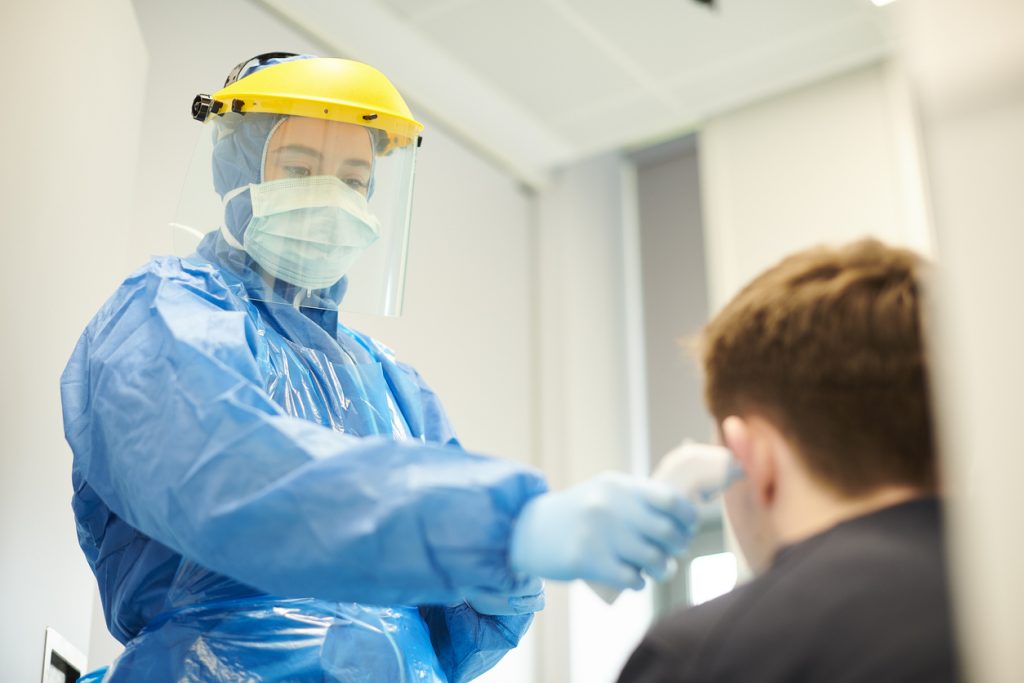

It seems unlikely that UK governments realised there could be circumstances where cuts in health and safety that damaged public health would ever be immediately and visibly obvious to the public and with such tragic effects. Now they are. The failures to plan for a pandemic and effectively protect the occupational health and safety of doctors, nurses, paramedics and other emergency workers treating patients have had major repercussions for the treatment of pandemic patients and for the workers themselves. The failures have included not only the lack of suitable and sufficient personal protective equipment and its rapid delivery but also staff shortages which put huge pressures on remaining staff in terms of fatigue and stress. This has been compounded by a significant number of doctors, nurses and allied health professionals either self-isolating or falling ill themselves. Hence the implications of the testing, tracing and lockdown policy failures are factors that damaged the NHS workforce directly and indirectly and so added to hazardous and risky NHS and social care working conditions.

Two defences could be made for what has happened in the UK. Firstly it might be argued that no pandemic had been foreseen or foreseen on the scale that COVID-19 has affected the world. This is not an argument easily defended as the coronaviruses were first identified in animals in the 1930s and then in humans in the 1960s. The particular coronavirus that emerged in 2019 could not have been foreseen but the effects of such viruses had been flagged repeatedly in 2005, 2009, 2015, 2019 and early 2020 by WHO and other organisations. Specific issues about the availability of PPE and the possibility of such viruses causing a pandemic were also widely recognised internationally . Numerous early warnings and indeed guides on what to do in the case of a pandemic were either ignored or only partially taken on board in the UK. There may well be evidence here of wilful ignorance in some Government and scientific civil servant responses.

A second defence could be that all the planning necessary for a pandemic had been done in the UK. It has been argued no country could have done more to protect the health and safety of its health care professional related workforce so that they would be able to treat and care for pandemic patients.

This defence is flawed because in 2005 the International Health Regulations bound every country to prioritize & dedicate domestic resources and recurrent spending for pandemic preparedness. This did not happen sufficiently between 2005 and 2020. UK flu preparation for example were found wanting in various respects in 2011, 2012, 2014, 2016. In 2017, the UK government apparently rejected advice to give PPE to all frontline NHS staff in a flu epidemic. In 2014, 2018, 2019 and early 2020 the WHO and ILO produced guides, manuals and even courses on planning and preparing for a pandemic all of which included making sure front-line health care staff had the PPE, equipment and resources they needed.

In 2020 the UK government manifestly had not prepared effectively for the pandemic and failed to act not just on early warnings including ones from China, South Korea and elsewhere but early global guides on how to safeguard health workers so they would then be able to safeguard the public and treat pandemic patients. The precautionary public health principle is geared to prevention and it is difficult to envisage a public health threat that could have warranted a more precautionary approach than a pandemic and one that required extensive testing, early lockdowns, and ample supplies of PPE. Yet the Government did not act.

We are still in the pandemic. So there is little justification for not now taking even greater steps to protect our health, emergency social care and key employees in ways that will not hinder or disrupt their work. This is of course the irony not recognised by our Government because good health and safety practices will safeguard these health workers who safeguard the public who safeguard our economy. The three elements are closely intertwined. The Health and Safety Executive responsible for UK workplace health and safety now states it wants to be flexible and proportionate in dealing with COVD-19. Yet the HSE appeared to go missing for weeks and months when the pandemic started. It is also difficult to envisage how a proportionate response to major failing in protecting doctors, nurses and social care workers often on our screens nightly could have been anything less than rapid interventions requiring immediate health and safety improvements.

This should mean early regulatory interventions in workplaces through inspections, monitoring, advice and support. PPE provision and adequate staffing levels, testing, the position of vulnerable workers outside healthcare and so on should all be considered health and safety matters. There should also be requirements on health and safety grounds that ministers, regulators and others provide details and timetables on PPE provision and testing and quantities; ensure proper consultation with workforces on pandemic planning; update the public, trade unions and the media regularly on how many health and other workers have been made ill or died from COVID caused or COVID related illnesses.

Pandemics cannot be avoided but COVID-19 has shown that the UK could and should have done a lot better to protect its workforce, protect the public and hence protect the economy too.