Marina Shapira, Lecturer in Quantitative Research Methods, Faculty of Social Sciences

Camilla Barnett, Research Assistant, Faculty of Social Sciences

Tracey Peace-Hughes, Research Fellow, Faculty of Social Sciences

Nicola Sturgeon famously said in 2015 that she should be judged on her record in tackling educational issues – especially her efforts to close Scotland’s persistent attainment gap between advantaged and disadvantaged young people. So it’s not a surprise that Scottish education has been a major talking point in the election campaign – centring on the Scottish government’s flagship education policy, the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE).

A rancorous debate has surfaced periodically in Scotland since 2015, focusing on allegedly falling attainment and narrower curriculum choice for secondary school pupils in their senior years. Now it has been reignited by a critical report by Jim Scott, an honorary professor at the University of Dundee, claiming that attainment in national qualifications at the age of 16 has plummeted under the SNP government.

Inevitably, this has been seized on by opposition politicians. Liz Smith MSP, the Conservative shadow education minister said:

The least able pupils are losing out most under Curriculum for Excellence. That is surely the most worrying trend, given that it was structured around key principles designed to do the exact opposite.

But, in our view, Professor Scott’s report is not a fair reflection of what has been happening in Scottish education. It has what we believe are methodological flaws that have led to results and claims that are very misleading.

Point of departure

The Curriculum for Excellence, which was introduced in the early years of this decade, is a shift away from learning dominated by teachers, focused purely on academic achievement and knowledge, towards a system designed to equip youngsters with flexible learning skills for life.

Based on four educational purposes – creating successful learners, responsible citizens, effective contributors and confident individuals – the curriculum strongly focuses the central role of learners and shifts the emphasis from the acquisition of knowledge/content to the development of skills. It is thus a very different approach to the one being taken south of the border.

Like Professor Scott, our recent publications have been critical of many aspects of this policy: the way it has been articulated and implemented – and particularly the trend towards curriculum narrowing for senior secondary pupils. Yet our analysis shows that attainment at the National 5 (typically ages 15-16) and Higher (17-18) levels has actually risen – both in terms of the overall percentage of passes and the proportion of pupils who achieved at least five passes at both levels.

So what is going on? Without addressing the full range of claims in the report, we’ll give you an example to illustrate our point. One of the claims in Scott’s report, which was widely reported in the Scottish media, was this: “attainment in Scottish [National levels 3 to 5] in S4 pupils has dropped by at least 32.9% for each level since CfE was introduced in 2013”.

The report uses Scottish Qualifications Authority official statistics to show that there were 335,397 passes in 2018-19 at National 3-5 levels, compared to 503,221 passes in 2012-2013. Simple maths thus suggests that the total number of passes in 2018-19 stands at 66.6% of the total number of passes in 2012-2013. Yet a drop in the total number of qualifications achieved is not necessarily evidence of a decline in attainment.

It is problematic to simply compare raw numbers from year to year unless you account for all changes between the baseline and other years. The reality is that students in Scotland are not entered for National 4 and 5 qualifications in the way that they used to be: for instance, the country has ended the widespread practice of double counting passes for each student at these two levels.

Students are also being put forward for fewer qualifications because the curriculum has been narrowed, typically from eight to six subjects in S4. At the same time, the size of the secondary school population has been continuously falling for the past ten years.

A better approach

To meaningfully compare the number of passes over time, you need to instead examine attainment as a proportion of the total number of entrants or awards for each year. When we did this, it showed that after the introduction of the CfE, there was a 15% increase in the proportion of passes at National 5 level. There was also a corresponding decrease in the proportion of passes at the lower National 3 level – suggesting that attainment has risen over the period as more students enter for and pass the higher-level qualification.

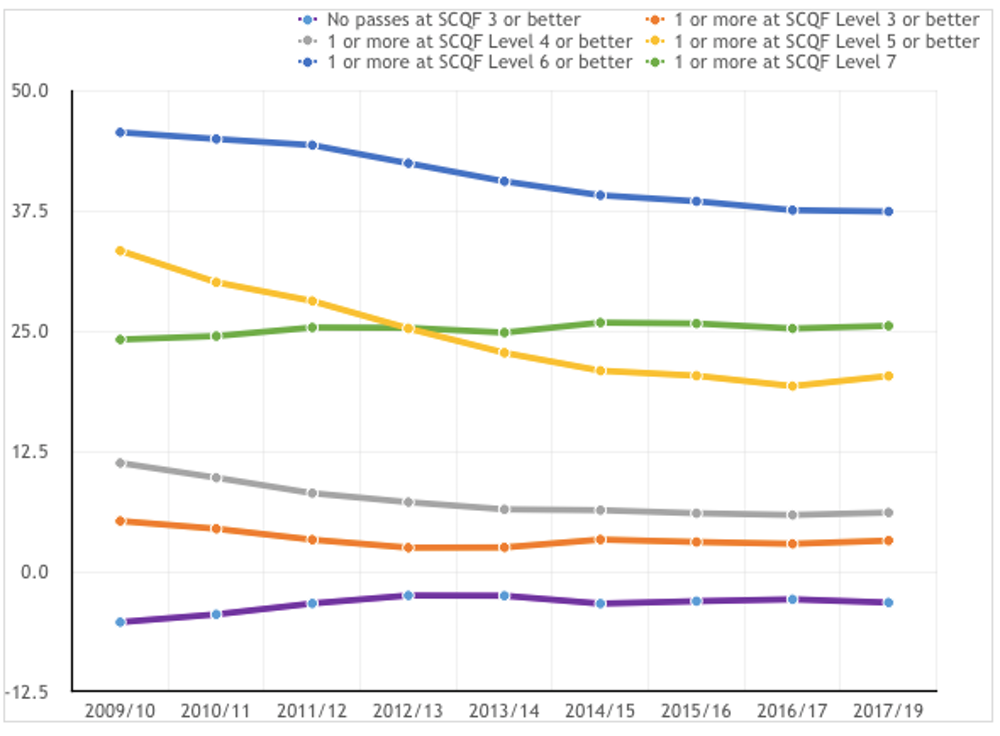

Scottish government data also shows that at National 4, 5 and Higher levels, attainment gaps between Scottish school leavers living in the most advantageous and most disadvantageous areas are getting smaller (see yellow, blue and grey lines in the chart below). Meanwhile, the gap between pupils in the most and least disadvantaged areas who leave school with no qualifications has remained – with small fluctuations – at about 3% since 2014-15 (see the purple line below).

The above analysis, which received some additional input from our colleagues Mark Priestley and Michelle Ritchie, hopefully illustrates the dangers of ill-informed political debate around education in Scotland – we go into more detail in this blog post.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to evaluate the CfE conclusively at this point in time. One of the arguments that we have been making in our recent work is that there is not enough evidence on the impacts of the policy yet. We need more research into everything from the breadth of education students are receiving to the number of A to C grades at National 5 and Higher levels to what happens in the years after people leave school.

Our new two-year research project, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, will go some way towards addressing this gap. We’ll combine the available administrative data with new research from social surveys, interviews and focus groups in secondary schools. In the meantime, the frustrating reality for voters is that any bold claims about the success or failure of the Scottish government’s approach to education must be taken with a large pinch of salt.

This article was first published on the Conversation, on 13th November 2019.