Dr Steve Rolfe, Research Fellow in Housing Studies, University of Stirling

Dr Lisa Garnham, Public Health Research Specialist, Glasgow Centre for Population Health

Considerable research to date has focused mainly on the detrimental impacts of homelessness or poor-quality housing. However, recent research led by academics at the University of Stirling demonstrates a number of ways in which different approaches to housing provision impact on tenants’ health and wellbeing.

Our findings show that there are a much broader set of pathways through which landlords and housing organisations can affect health and wellbeing. Most importantly, we found that tenants’ health and wellbeing is shaped by whether they feel at home in their tenancy, and this is underpinned by four key foundations:

- Relationships. Tenants do better when they have a named member of staff, who respects and understands their individual needs, history and situation.

- Property quality. Beyond the basics of a defect-free, efficient property, tenants need to be able to make their property feel like home. For some the ideal is an empty, blank canvas that they can customise. For others, it is much harder to make a home if the property is unfurnished and undecorated and they do not have practical or financial support.

- Affordability. Reasonable rent levels are important, but there are other financial factors at the start of a tenancy which can have a substantial effect on tenants’ wellbeing. Help to deal with benefits, utility costs, refurbishment expenses, deposits and arrears is key.

- Neighbourhood. Tenants settle more easily into their property if they have as much choice as possible about where they live and are supported to find the right property in the right place where they feel safe and a sense of belonging.

These four foundations apply across both the social and private rented sectors. Where housing providers get these four aspects right, tenants experience significant improvements in health and wellbeing.

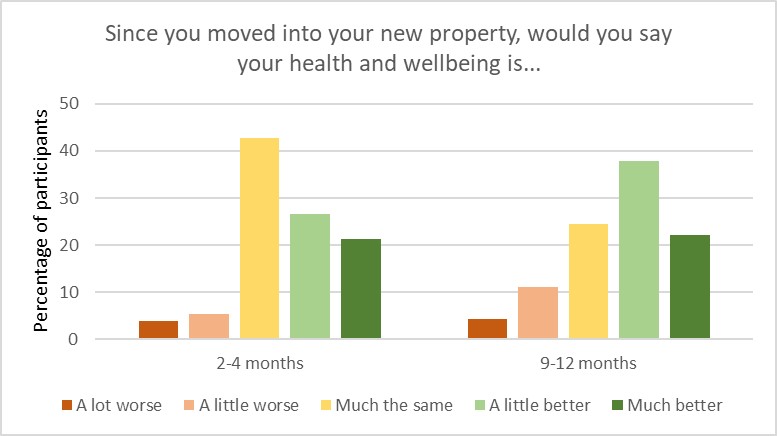

Figure 1 – Health and wellbeing change from start of tenancy

On the basis of these findings, we held a co-production event with around 60 housing professionals, policy-makers, public health practitioners and tenants, to produce meaningful and practical recommendations. The discussions focused primarily on Scotland, but many of the recommendations are applicable elsewhere. The overarching themes of these recommendations were:

Focus on health and wellbeing of tenants

Everybody understands that housing shapes the health of those who live in it, but there is less recognition of the broader role of housing providers and the different housing sectors as social determinants of health. Hence, there is a need for organisations across the housing and public health sectors to raise awareness of these issues and to ensure that tenants needs are at the forefront of housing providers’ concerns.

Relationships and communication

Cutting right across our findings was the key message that tenants did much better in their new tenancy when they had a good relationship with their housing provider. Housing organisations need to consider how they can support front-line staff to build and manage relationships which are person-centred and not just neutral ‘customer service’, in order to manage the diversity of needs and expectations amongst their tenants. This in turn requires a focus from policy makers on funding for tenancy support.

Property quality

Substantial improvements in property standards have been made in recent years, particularly in the social housing sector through the Scottish Housing Quality Standard. However, there are still issues with property quality in the private rented sector (PRS), as well as a need to recognise that tenants need more than a basic, water-tight dwelling to make a home. Changes to regulation and funding are required to improve property quality across the housing sectors, to a standard which includes aspects such as décor and furnishing.

Finance and affordability

Most of the focus in debates about housing affordability focuses on the cost of buying a home or the level of rent in the PRS. Our research highlighted the ways in which other housing-related costs and the financial chaos instigated by a change of tenancy can be more important than rent in generating stress for tenants, leading to significant health and wellbeing issues. A number of changes are needed in policy and practice to smooth this financial transition for tenants.

Tenant participation and empowerment

Whilst social housing organisations have statutory duties to engage with tenants, the same is not true in the PRS. Given the substantial growth in the PRS since the turn of the century, there is a clear need to review tenant participation requirements, to give all tenants a collective voice.

Organisational standards and regulation

All of our recommendations will require a significant focus on training and regulatory standards across both social housing and the PRS. There are many examples of good practice, but policy makers need to raise the bar for all housing organisations, letting agents and landlords.

The detail of our recommendations can be found here. Put into practice, they have the potential to generate significant public health impacts through changes to housing provision and play a substantial role in reducing health inequalities. Tenants in social housing and in cheaper parts of the PRS are particularly vulnerable to the detrimental impacts of housing on health and wellbeing because of their constrained options within the housing market and limited power within their housing situation.

Improving housing provision for these tenants has the potential to improve the health and wellbeing of some of the most disadvantaged groups in society, closing the gap to those who already benefit from a comfortable, secure home environment.

The study was led by:

- Dr Steve Rolfe, Research Fellow in Housing Studies, University of Stirling

- Dr Lisa Garnham, Public Health Research Specialist, Glasgow Centre for Population Health

The project team also included:

- Professor Isobel Anderson, Professor of Housing Studies, University of Stirling

- Professor Cam Donaldson, Yunus Chair in Social Business and Health, Glasgow Caledonian University

- Professor Jon Godwin, Professor of Statistics, Glasgow Caledonian University

- Dr Pete Seaman, Acting Associate Director, Glasgow Centre for Population Health